What causes brake rotor warp

What causes brake rotor warp

Brake rotor warp — there’s no such thing

When people talk about brake rotor warp, it’s usually because they’re experiencing a brake pedal pulsation or “judder.” They call it warp because it’s a common myth that heavy braking can warp a brake rotor.

Brake rotors DO NOT WARP

There isn’t a vehicle braking system around that can produce the 2,300°F temperature needed to warp a brake rotor. Seriously! See the temperature chart below to see what happens when brakes overheat.

Brake pedal pulsation is NOT caused by brake rotor warp

But brake pedal pulsation is actually caused by disc thickness variation due to lateral runout, not actual rotor warp. That’s because, while brake rotors can overheat from heavy use, they don’t warp from that kind of heat because it’s simply not high enough to warp cast iron. Here’s the point: brakes CAN generate enough heat to overheat and discolor a brake rotor, but they CAN’T generate enough heat to warp a brake rotor.

Let’s talk brake temperatures and warp

During normal street use, brake pads generate 200°F to 400°F. Beyond 400°F the resins in the brake pad material being to “boil” and off-gas. That off-gassing actually pushes the brake pad away from the rotor surface causing “brake fade.” So your brakes will start to fade long before they reach anywhere near the temperature needed to soften and warp the brake rotor.

Here are some noteworthy brake pad temperatures and the effects of those temperatures

At 570°F – 662°F OEM and aftermarket street-use brake pads begin to fade and reduce braking to almost zero. If you haven’t experienced a loss of braking but you have brake pedal pulsation, it’s not due to warped rotors.

At 850°F Brake pads begin to smoke. Again, 850°F is not enough to warp a rotor.

At 1,100°F Brake pad friction material begins to oxidize

At 1,200°F brake pad friction material begins to carbonize.

At 1,400°F you’re finally reaching the point where you overheat the rotor and cause discoloration. When examining the brakes, you would see severe pad glazing, carbonization and oxidation.

To warp a rotor, you have to change the metallurgy and that takes almost 2,000°F. There’s no street vehicle braking system that can generate that kind of heat

Here are the melting temps of cast iron brake rotors

In order for a brake rotor to warp, it must soften. You’d have to generate brake temperatures of 2,000°F to cause warp. If that happened, you’d also see rotor discoloration and brake pad destruction.

G3000 Gray Cast Iron Melt temperature 1145°C 2093°F Most common material for brake rotors

G4000 Gray Cast Iron Melt temperature 1145°C 2093°F Most common material for brake rotors

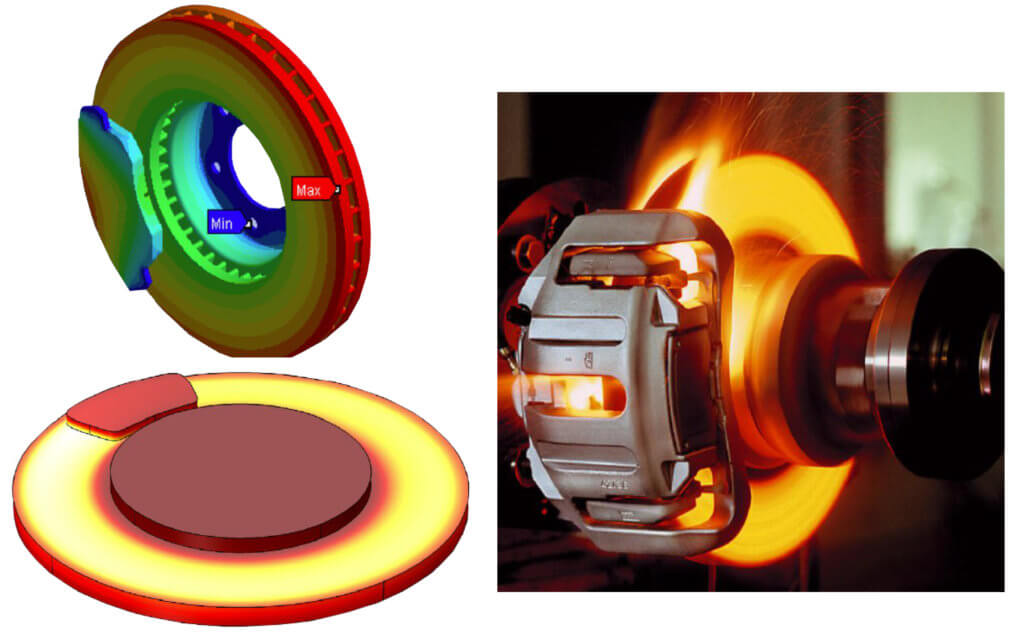

Brake rotor temperature distribution

As long as both brake pads are exerting equal force on the rotor face, both inboard and outboard rotor faces will have the same temperature. As you can see in these brake rotor temperature illustrations, the greatest rotor heat is at the outer circumference of the rotor, not the face. The reason for this hot zone is because the cooling fins are moving the heat from the inside diameter to the outermost circumference of the rotor.

Brake rotor heat distribution

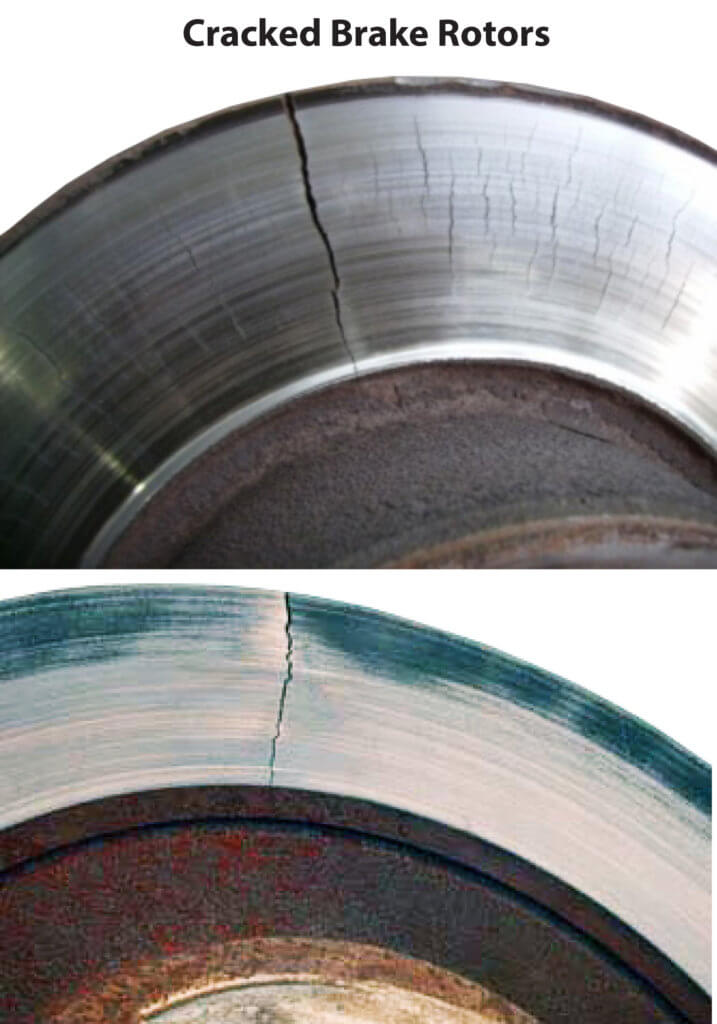

What about rotor quenching (hitting water after heavy braking) causing warp?

The theory is that you overheat a rotor through heavy braking and then hit a puddle which causes the rotor to warp. When hot metal is quickly quenched by hitting water, it contracts. Quenching far more likely to crack the rotor in that situation than to warp it.

Just like hot glass that’s quenched by water, the internal stresses in a rotor will cause the metal to crack. Even then, you’d still see the signs of overheating; burned pads, and possible discoloration. Cracking after overheating is far more common than warping.

If the brake pads aren’t charcoal, then your brakes never reached a temperature high enough to warp the rotors.

Rotor warp is actually disc thickness variation

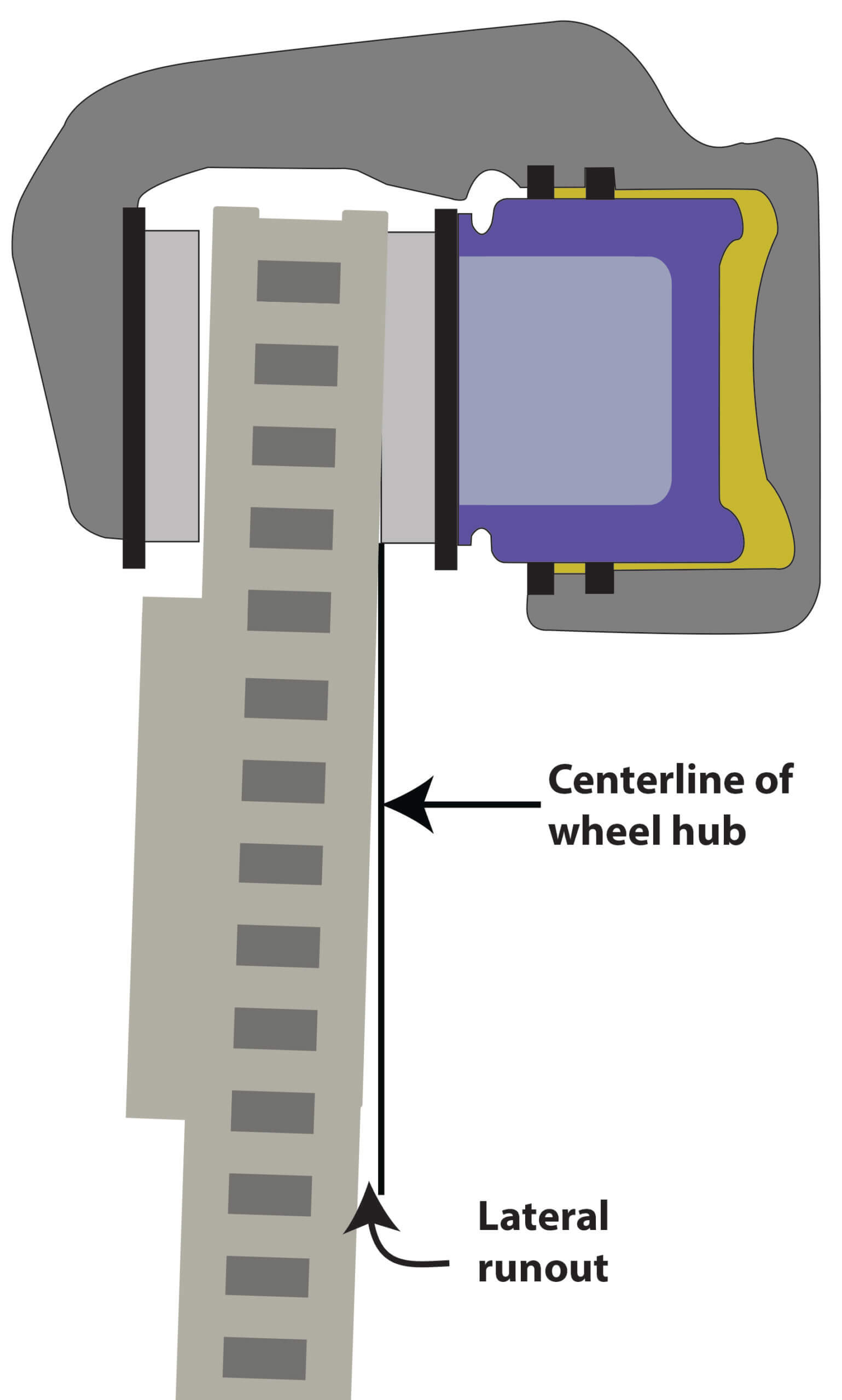

Let’s look at what causes brake pedal pulsation and why it’s confused with brake rotor warp. The brake caliper is mounted to the steering knuckle or rear knuckle. In order for the brakes to work as designed, the brake rotor must be perfectly parallel with the wheel hub, knuckle, and caliper.

Brake rotor lateral runout

However, if the wheel hub is corroded or the lug

When the brake rotor doesn’t sit perfectly parallel with the wheel hub and is cocked, you get lateral runout where opposite sides of the rotor hit just one brake pad

nuts are improperly torqued, the rotor can sit perfectly parallel with the wheel hub. The result is lateral runout.

If the image to the right you see that the brake rotor isn’t perfectly parallel with the wheel hub. When rotating, one side of the rotor face hits the inboard brake pad while the opposite side barely touches or doesn’t touch the outboard brake pad.

Depending on the type of friction material used, the inboard brake pad can either leave a deposit of friction material film on the rotor or wear it away. Adherent brake pads leave an extra deposit of film, while abrasive brake pads wear away the rotor.

When the rotor makes a 180° rotation, the opposite occurs; the outboard pad leaves an extra film or wears the rotor while the inboard pad barely touches the rotor face.

This added film thickness or wear is referred to as disc thickness variation (DTV).

Disc thickness variation

How much lateral runout does it take to create enough deposit formation or wear and DTV? Not much. As little as .006 lateral runout can cause brake pedal pulsation and it happens in as little as 3,000 miles after installing new brakes and rotors.

Most common causes of lateral runout and DTV

Not cleaning the wheel hub before installing the rotor

A corroded wheel hub can cause lateral runout, disc thickness variation, and brake pedal pulsation.

Cleaning the wheel hub to remove corrosion ensures a parallel fit between the rotor and the hub.

Not cleaning corrosion off the inside of the rotor hat

Use a polishing pad to remove corrosion in the rotor hat area

Not using a torque wrench to tighten lug nut

If the lug nut torque is uneven, it can cock the rotor, causing lateral runout.

A worn wheel bearing can also cause repeat brake pedal pulsation

Again, the rotor must be perfectly parallel with the wheel hub in order to run true. But what if the wheel bearing is worn and the wheel hub isn’t true to the steering knuckle that holds the brake caliper?

In that cause, the rotor will have lateral runout compared to the caliper. That will either wear opposite sides of the rotor (if you use abrasive friction material) or have pad deposits on opposite sides of the rotor (if you use adherent brake pads).

Check wheel bearing using a dial indicator to check for lateral runout.

©, 2021 Rick Muscoplat

Posted on by Rick Muscoplat